You might be surprised by how little we understand about the Earth’s inner mechanisms. While we have a good grasp of the upper layers that form mountains and cause earthquakes, the deeper layers remain mysterious.

One hotly debated topic over the past few decades has been the movement of the Earth’s inner core. Is it moving forwards, backwards, or side to side? Until recently, no one knew for sure. However, a new study published in Nature may have finally resolved this debate. The research suggests that the core is moving backwards relative to the Earth’s surface, supporting a controversial study from last year by Peking University researchers published in Nature Geoscience.

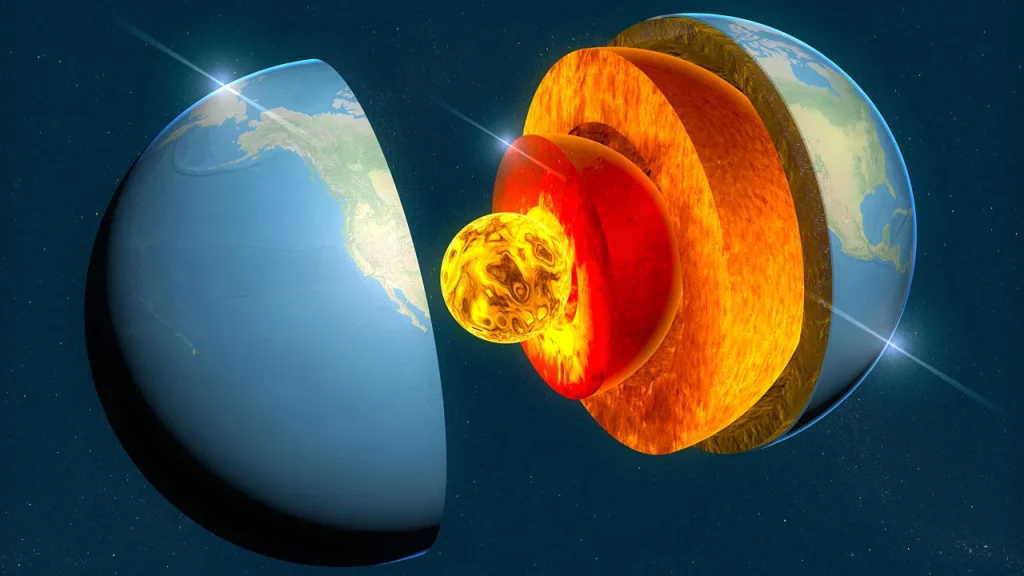

The Earth’s inner core is a solid, crystallized iron sphere about the size of the Moon, floating nearly 5,000 kilometers below the surface in a sea of liquid iron, nickel, and other metals known as the outer core.

“Because the inner core is solid and floats in the outer core, nothing holds it in place,” explained Prof John Vidale, a researcher at the University of Southern California (USC) and co-author of the study, to BBC Science Focus.

“We’ve known since the 1990s that the movement of the inner core has been changing in some combination, and we’ve been debating how it’s changing,” Vidale said.

According to a USC press release, the new study provides “unambiguous evidence” that the inner core began to slow down around 2010, moving slower than the Earth’s surface. This creates the illusion of the core moving backwards relative to the surface, similar to how a car that slows down appears to move backwards to a driver maintaining a constant speed.

If accurate, this would mark the first observed slowdown in 40 years and support the theory that the core’s speed changes in 70-year cycles.

To detect these changes, the team studied repetitive earthquakes, specifically 121 quakes in the South Sandwich Islands between 1991 and 2023, using seismographs in Canada and Alaska. They also analyzed data from Soviet-era nuclear tests.

Vidale and his team searched for matching seismic waveforms from different times. If the inner core rotates independently of the rest of the Earth, waves from recurring quakes would pass through different regions of the core, creating unique waveforms due to its uneven structure.

Conversely, if the core had reversed its rotation, some waveforms should match those from before the reversal, indicating the core had realigned with its previous path.

“When I first saw the seismograms hinting at this change, I was stumped,” Vidale said. “But when we found two dozen more observations showing the same pattern, the result was clear: the inner core had slowed down for the first time in many decades. Other scientists have proposed similar and different models, but our latest study provides the most convincing resolution.”

At the surface level, the effects are uncertain, though Vidale noted it could slightly alter the length of our day by about a thousandth of a second, almost imperceptible amid the noise of the churning oceans and atmosphere.

Future work for the team includes measuring more waveforms from different locations and paths through the planet. “Part of it is just waiting. The core is moving back through some positions where it did some unusual things around 2001, so we’ll try figuring out what that was,” Vidale concluded.